Articles liés à I May Not Get There With You: The True Martin Luther...

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

"I Saw That Dream Turn Into a Nightmare":

From Color-Blindness to Black Compensation

"I am a mother with six kids," says the beautiful ebony-skinned woman adorned in batik-print African dress and silver loop earrings. "And part of the time I don't even know where I'm going to get the next meal for my children."

All Martin Luther King, Jr., can do is shake his head and utter, "My, my."

King was on a 1968 swing through rural, poor parts of the black South, drumming up support for his Poor People's March on Washington later that year. He had stopped at a small white wood-frame church in Mississippi to press his case, and to listen to the woes of the poor. A painting of a white Jesus, nearly ubiquitous in black churches, observed their every move. Later King would absorb more tales of Mississippi's material misery.

"People just don't know, but it's really hard," a poor woman in church pleads. "Not only me, there's so many more that's in the same shape. I'm not the only one. It's just so many right around that don't have shoes, clothes, is naked and hungry. Part of the time, you have to fix your children pinto beans morning, dinner and supper. They don't know what it is to get a good meal." King is visibly moved.

"You all are really to be admired," he compassionately offers, "and I want you to know that you have my moral support. I'm going to be praying for you. I'm going to be coming back to see you and we are going to be demanding, when we go to Washington, that something be done and done immediately about these conditions."

King couldn't keep that promise; his life would be snuffed out a mere three weeks before his massive campaign reached its destination. But King hammered home the rationale behind his attempt to unite the desperately poor. He understood that the government owed something to the masses of black folk who had been left behind as America parceled out land and money to whites while exploiting black labor.

"At the very same time that America refused to give the Negro any land," King argues, "through an act of Congress our government was giving away millions of acres of land in the West and the Midwest, which meant it was willing to undergird its white peasants from Europe with an economic floor." Building a full head of steam, King rolls his rhetoric down the track of just compensation for blacks by contrasting even more sharply the unequal treatment of the races in education, agriculture, and subsidies.

"But not only did they give them land," King's indictment speeds on, "they built land grant colleges with government money to teach them how to farm. Not only that, they provided county agents to further their expertise in farming. Not only that, they provided low interest rates in order that they could mechanize their farms."

King links white privilege and governmental support directly to black suffering, and thus underscores the hypocrisy of whites who have been helped demanding that blacks thrive through self-help.

"Not only that," King says in delivering the death blow to fallacies about the black unwillingness to work, "today many of these people are receiving millions of dollars in federal subsidies not to farm, and they are the very people telling the black man that he ought to lift himself by his own bootstraps. And this is what we are faced with, and this is the reality."

With one final fell swoop, King reinforces his identification with the destitute, reiterates his belief that the government has failed in its fiduciary obligations to blacks, and subverts the stereotype of blacks shiftlessly waiting around for government cash by insisting that blacks deserve what is coming to them.

"Now, when we come to Washington in this campaign, we are coming to get our check."

This is not the King whom conservatives have used to undermine progressive politics and black interests. Indeed, conservatives must be applauded for their perverse ingenuity in coopting King's legacy and the rhetoric of the civil rights movement. Unlike the radical right, whose racist motivations are hardly obscured by painfully infrequent references to racial equality, contemporary conservatives often speak of race in moral terms gleaned from the black freedom struggle. Thus, while the radical right is open about its disdain for social upheaval in the sixties, many conservatives pretend to embrace a revolution they in fact bitterly opposed. This is especially troubling because of the moral assault by conservatives on civil rights activists who believe that affirmative action, for instance, is part of the ongoing attack on discrimination. These same conservatives rarely target the real enemies of racial equality: newfangled racists who drape their bigotry in scientific jargon or political demagoguery. Instead, they hurl stigma at civil rights veterans who risked great peril to destroy a racist virus found even in the diseased body of ultraconservatism. Perhaps most insidious, conservatives rarely admit that whatever racial enlightenment they possess likely came as blacks and their allies opposed the conservative ideology of race. The price blacks paid for such opposition was abrupt dismissal and name calling: they were often dismissed as un-American, they were sometimes ridiculed as agents provocateurs of violence, and they were occasionally demonized as social pariahs on the body politic.

Worse still, when the civil rights revolution reached its zenith and accomplished some of its goals -- including recasting the terms in which the nation discussed race -- many conservatives recovered from the shock to their system of belief by going on the offensive. The sixties may have belonged to the liberals, but the subsequent decades have been whipped into line by a conservative backlash. After eroding the spirit of liberal racial reform, conservatives have breathed new life into the racial rhetoric they successfully forced the liberals to abandon. Now terms like "equal playing field," "racial justice," "equal opportunity," and, most ominous, "color-blind" drip from the lips of formerly stalwart segregationist politicians, conservative policy wonks, and intellectual hired guns for deep-pocketed right-wing think tanks. Crucial concepts are deviously turned inside out, leaving the impression of a cyclone turned in on itself. Affirmative action is rendered as reverse racism, while goals and timetables are remade, in sinister fashion, into "quotas." This achievement allows the conservatives to claim that they are opposed to the wrong-headed results of the civil rights movement, even as they claim to uphold its intent -- racial equality. Hence, conservatives seize the spotlight and appear to be calm and reasonable about issues of race. In their shadows, liberals and leftists are often portrayed as unreasonable and dishonest figures who uproot the grand ideals of the civil rights movement from its moral ground.

At the heart of the conservative appropriation of King's vision is the argument that King was an advocate of a color-blind society. Hence, any policy or position that promotes color consciousness runs counter to King's philosophy. Moreover, affirmative action is viewed as a poisonous rejection of King's insistence that merit, not race, should determine how education and employment are distributed. The wellspring of such beliefs about King is a singular, golden phrase lifted from his "I Have a Dream" speech. "I have a dream," King eloquently yearned, "my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character." Of the hundreds of thousands of words that King spoke, few others have had more impact than these thirty-four, uttered when he was thirty-four years old, couched in his most famous oration. Tragically, King's American dream has been seized and distorted by a group of conservative citizens whose forebears and ideology have trampled King's legacy. If King's hope for radical social change is to survive, we must wrest his complex meaning from their harmful embrace. If we are to combat the conservative misappropriation of King's words, we must first understand just how important -- and problematic -- King's speech has been to American understandings of race for the past thirty years.

As a nine-year-old boy, I saved money from odd jobs and sent off for a 45-rpm record containing excerpts of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s greatest speeches. Since King had been dead for only a few weeks and since I'd first heard about him the evening he was murdered, his recorded speeches had a great impact on me. Hearing the passionate words that King delivered as much as a decade earlier didn't at all diminish their powerful hold on my youthful imagination. I listened to his speeches over and over until his words were scorched into my brain. All I'd have to do was hear the beginning of a King excerpt, and I could immediately conjure the speech and the tumultuous verbal support of his adoring audience. King was constantly interrupted by a sweetly bellowed stream of "all right," "tell the truth," "yes, sir," "un hunh," "go 'head," "preach," "hah hah," and "speak." Besides "I See the Promised Land" -- King's searing last speech that interweaved premonition of his death and the promise of black deliverance -- I was thrilled the most by "I Have a Dream." King's best-known refrain echoed the longest on my recording since the compiler must have believed that it was King's most important speech.

"I Have a Dream" continues to draw millions around the globe to its hopeful vision of racial harmony. It is easy to see that many Americans identify with King through that speech. Many can recall where they were when it was delivered. Still others recall how reading that speech helped to locate them on the map of racial conscience. In a recent survey of the fifty most anthologized essays in American culture over the last half-century, "I Have a Dream" made the top ten list. King's towering oration shines alongside the essays of Jonathan Swift, Thomas Jefferson, and E. B. White. And as it skillfully did for me thirty years ago, "I Have a Dream" brings black suffering to the surface and tells us how racial healing can be embraced.

Of course, hearing that speech as a boy thirty years ago and hearing it now as a man makes a world of difference. King's radical tones are clearer. His rebellious flourishes defiantly leap to the foreground. And his dismay at America for denying prosperity to millions of blacks is now more sharply focused. Today I read even his labored restraint as a gesture of profound protest. We have surrendered to romantic images of King at the Lincoln Memorial inspiring America to reach, as he reached with outstretched arms, for a better future. All the while we forget his poignant warning against gradual racial progress and his remarkable threat of revolution should our nation fail to keep its promises. Still, like all other great black orators, King understood the value of understating and implying difficult truths. He knew how to drape hard realities in soaring rhetoric that won the day because it struck the right balance of outrage and optimism. To be sure, we have been long on King's optimism while shortchanging his outrage.

In ways that King could never have imagined -- indeed, in a fashion that might make him spin in his grave -- "I Have a Dream" has been used to chip away at King's enduring social legacy. One phrase has been pinched from King's speech to justify assaults on civil rights in the name of color-blind policies. Moreover, we have frozen King in a timeless mood of optimism that later that very year he grew to question. That's because we have selectively listened to what King had to say to us that muggy afternoon. It is easier for us to embrace the day's warm memories than to confront the cold realities that led to the March on Washington in the first place. August 28, 1963, was a single moment in time that captured the suffering of centuries. It was an afternoon shaped as much by white brutality and black oppression as by uplifting rhetoric. We have chosen to forget how our nation achieved the racial progress we now enjoy.

In the light of the determined misuse of King's rhetoric, a modest proposal appears in order: a ten-year moratorium on listening to or reading "I Have a Dream." At first blush, such a proposal seems absurd and counterproductive. After all, King's words have convinced many Americans that racial justice should be aggressively pursued. The sad truth is, however, that our political climate has eroded the real point of King's beautiful words. We have been ambushed by bizarre and sophisticated distortions of King's true meaning. If we are to recover the authentic purposes of King's address, we must dig beneath his words into our own social and moral habits. Only then can the animating spirit behind his words be truly restored. If we have been as deeply marked by his words as we claim, we need not fear that by putting away his speech we are putting away his ideals. After all, his ideals will have penetrated the very fabric of our personal and public practice. If King's speech has failed to reshape our racial politics sufficiently, it might be a good idea to huddle and ask where we have gone wrong. In the long run, we will do more to preserve King's moral aims by focusing on what he had in mind and how he sought to achieve his goals. That doesn't mean that King's words are scripture or that we cannot differ with him about his beliefs or strategies. We might, however, lower the likelihood of King's words being crudely snatched out of context and used by forces that he strongly opposed.

The great consolation to giving up "I Have a Dream" is that we pay attention to King's other writings and orations. Out of sheer neglect, most of his other works have been cast aside as rhetorical stepchildren. After devoting a decade to King's other works, especially his trenchant later speeches, we will grasp the true scope of his social agenda. We will also understand how King constantly refined his view of the American dream. As things stand, "I Have a Dream" has been identified as King's definitive statement on race. To that degree it has become an enemy to his moral complexity. It alienates the social vision King expressed in his last four years. The overvaluing and misreading of "I Have a Dream" has skillfully silenced a huge dimension of King's prophetic ministry.

Before putting away King's address and before attending to his other speeches, it will be useful to acknowledge "I Have a Dream's" true greatness and read it through the lens of King's mature struggles. True enough, on August 28, 1963, King stood at the sunbathed peak of racial transformation and at the height of his magical oratorical powers. King summoned resources of hope that took wing on carefully chosen words. He turned the Lincoln Memorial into a Baptist sanctuary and preached an inspiring sermon. "I Have a Dream" is unquestionably one of the defining moments in American civic rhetoric. Its features remain remarkable: The eloquence and beauty of its metaphors. The awe-inspiring reach of its civic ideals. Its edifying call for spiritual and moral renewal. Its appeal to transracial social harmony. Its graceful embrace of militancy and moderation. Its soaring expectations of charity and justice. Its inviolable belief in the essential goodness of our countrymen. These themes and much more came out that day.

King's delivery was equally majestic. His lilting cadences stretched along a spiral of intermittent sonic crescendoes. His trumpet-like baritone measured the pulse of his audience's fervor. He evoked his congregation's spiritual longing in sounds as tangy as Souther...

Jake Lamar The New York Observer Not simply an important book -- it is a necessary one. In prose that is always sharp and engaging, Dyson uses King's life and legacy to take on everything from contemporary conservatism to hip-hop culture...An indispensable contribution to American social criticism.

Paul Rosenberg The Denver Post Masterfully, Dyson...seamlessly combines a passionate exploration of King's battles, values and ideas with a highly nuanced picture of the contexts he struggled in and transformed, then draws parallels and contrasts to our world today. Like King himself, the result speaks to everyone, from ivory tower to hip-hop streets, challenging all of us to move beyond our present limitations.

Michael Fletcher The Washington Post Such is the genius of Dyson. He...flows freely from the profound to the profane, from popular culture to classical literature...Dyson's latest book should only enhance his reputation...The book resurrects a King who bears little resemblance to the sainted -- some say homogenized -- integrationist fixed in the national consciousness.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurFree Press

- Date d'édition2000

- ISBN 10 0684867761

- ISBN 13 9780684867762

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages240

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 3,69

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

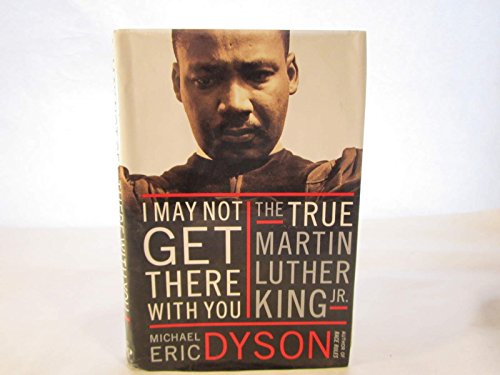

I May Not Get There with You: The True Martin Luther King, Jr.

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_0684867761

I May Not Get There with You: The True Martin Luther King, Jr.

Description du livre Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur FrontCover0684867761

I May Not Get There with You: The True Martin Luther King, Jr.

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. Brand New Copy. N° de réf. du vendeur BBB_new0684867761

I May Not Get There with You: The True Martin Luther King, Jr.

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard0684867761

I May Not Get There with You: The True Martin Luther King, Jr.

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. Buy for Great customer experience. N° de réf. du vendeur GoldenDragon0684867761

I May Not Get There with You: The True Martin Luther King, Jr.

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. Prompt service guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur Clean0684867761

I May Not Get There with You: The True Martin Luther King, Jr.

Description du livre Etat : New. Book is in NEW condition. 1.46. N° de réf. du vendeur 0684867761-2-1

I May Not Get There with You: The True Martin Luther King, Jr.

Description du livre Etat : New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 1.46. N° de réf. du vendeur 353-0684867761-new

I May Not Get There with You: The True Martin Luther King, Jr.

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. Arguing that Martin Luther King, Jr., should stand beside the Founding Fathers in terms of his significance to American history, the author serves up a compelling portrait of a personally flawed but nevertheless great leader. N° de réf. du vendeur DADAX0684867761

I May Not Get There with You: The True Martin Luther King, Jr.

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think0684867761