Articles liés à The Nurture Assumption: Why Children Turn Out the Way...

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

Heredity and environment. They are the yin and yang, the Adam and Eve, the Mom and Pop of pop psychology. Even in high school I knew enough about the subject to inform my parents, when they yelled at me, that if they didn't like the way I was turning out they had no one to blame but themselves: they had provided both my heredity and my environment.

"Heredity and environment" -- that's what we called them back then. Nowadays they are more often referred to as "nature and nurture." Powerful as they were under the names they were born with, they are yet more powerful under their alliterative aliases. Nature and nurture rule. Everyone knows it, no one questions it: nature and nurture are the movers and shapers. They made us what we are today and will determine what our children will be tomorrow.

In an article in the January 1998 issue of Wired, a science journalist muses about the day -- twenty? fifty? a hundred years from now? -- when parents will be able to shop for their children's genes as easily as today they shop for their jeans. "Genotype choice," the journalist calls it. Would you like a girl or a boy? Curly hair or straight? A whiz at math or a winner of spelling bees? "It would give parents a real power over the sort of people their children will turn out to be," he says. Then he adds, "But parents have that power already, to a large degree."

Parents already have power over the sort of people their children will turn out to be, says the journalist. He means, because parents provide the environment. The nurture.

No one questions it because it seems self-evident. The two things that

determine what sort of people your children will turn out to be are nature -- their genes -- and nurture -- the way you bring them up. That is what you believe and it also happens to be what the professor of psychology believes. A happy coincidence that is not to be taken for granted, because in most sciences the expert thinks one thing and the ordinary citizen -- the one who used to be called "the man on the street" -- thinks something else. But on this the professor and the person ahead of you on the checkout line agree: nature and nurture rule. Nature gives parents a baby; the end result depends on how they nurture it. Good nurturing can make up for many of nature's mistakes; lack of nurturing can trash nature's best efforts.

That is what I used to think too, before I changed my mind.

What I changed my mind about was nurture, not environment. This is not going to be one of those books that says everything is genetic; it isn't. The environment is just as important as the genes. The things children experience while they are growing up are just as important as the things they are born with. What I changed my mind about was whether "nurture" is really a synonym for "environment." Using it as a synonym for environment, I realized, is begging the question.

"Nurture" is not a neutral word: it carries baggage. Its literal meaning

is "to take care of" or "to rear"; it comes from the same Latin root that

gave us nourish and nurse (in the sense of "breast-feed"). The use of "nurture" as a synonym for "environment" is based on the assumption that what influences children's development, apart from their genes, is the way their parents bring them up. I call this the nurture assumption. Only after rearing two children of my own and coauthoring three editions of a college textbook on child development did I begin to question this assumption. Only recently did I come to the conclusion that it is wrong.

It is difficult to disprove assumptions because they are, by definition, things that do not require proof. My first job is to show that the nurture assumption is nothing more than that: simply an assumption. My second is to convince you that it is an unwarranted assumption. My third is to give you something to put in its place. What I will offer is a viewpoint as powerful as the one it replaces -- a new way of explaining why children turn out the way they do. A new answer to the basic question of why we are the way we are. My answer is based on a consideration of what kind of mind the child is equipped with, which requires, in turn, a consideration of the evolutionary history of our species. I will ask you to accompany me on visits to other times and other societies. Even chimpanzee societies.

Beyond a Reasonable Doubt?

How can I question something for which there is so much evidence? You can see it with your own eyes: parents do have effects on their kids. The child who has been beaten looks cowed in the presence of her parents. The child whose parents have been wimpy runs rampant over them. The child whose parents failed to teach morality behaves immorally. The child whose parents don't think he will accomplish much doesn't accomplish much.

For those doubting Thomases who have to see it in print, there are books full of evidence -- thousands of books. Books written by clinical psychologists like Susan Forward, who describes the devastating and longlasting effects of "toxic parents" -- overcritical, overbearing, underloving, or unpredictable people who undermine their children's self-esteem and autonomy or give them too much autonomy too soon. Dr. Forward has seen the damage such parents wreak on their children. Her patients are in terrible shape psychologically and it is all their parents' fault. They won't get better until they admit, to Dr. Forward and themselves, that it is all their parents' fault.

But perhaps you are among those doubting Thomases who don't consider the opinions of clinical psychologists, formed on the basis of conversations with a self-selected sample of troubled patients, to be evidence. All right, then, there is evidence of a more scientific sort: evidence obtained in carefully designed studies of ordinary parents and their children -- parents and children whose psychological well-being varies over a wider range than you could find in Dr. Forward's waiting room.

In her book It Takes a Village, First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton has summarized some of the findings from the carefully designed studies carried out by developmental psychologists. Parents who care for their babies in a loving, responsive way tend to have babies who are securely attached to them and who develop into self-confident, friendly children. Parents who talk to their children, listen to them, and read to them tend to have bright children who do well in school. Parents who provide firm -- but not rigid -- limits for their children have children who are less likely to get into trouble. Parents who treat their children harshly tend to have children who are aggressive or anxious, or both. Parents who behave in an honest, kind, and conscientious manner with their children are likely to have children who also behave in an honest, kind, and conscientious manner. And parents who fail to provide their children with a home that contains both a mother and a father have children who are more likely to fail in some way in their own adult lives.

These statements, and others of a similar sort, are not airy speculation. There is a tremendous amount of research to back them up. The textbooks I wrote for undergraduates taking college courses in child development were based on the evidence produced by that research. The professors who teach the courses believe the evidence. So do the journalists who occasionally report the results of a study in a newspaper or magazine article. The pediatricians who give advice to parents base much of their advice on it. Other advice-givers who write books and newspaper articles also take the evidence at face value. The studies done by developmental psychologists have an influence that ripples outward and permeates our culture.

During the years I was writing textbooks, I believed the evidence too. But then I looked at it more closely and to my considerable surprise it fell apart in my hands. The evidence developmental psychologists use to support the nurture assumption is not what it appears to be: it does not prove what it appears to prove. And there is a rising tide of evidence against the nurture assumption.

The nurture assumption is not a truism; it is not even a universally acknowledged truth. It is a product of our culture -- a cherished cultural myth. In the remainder of this chapter I will tell you where it came from and how I came to question it.

The Heredity and Environment of the Nurture Assumption

Francis Galton -- Charles Darwin's cousin -- is the one who usually gets the credit for coining the phrase "nature and nurture." Galton probably got the idea from Shakespeare, but Shakespeare didn't originate it either: thirty years before he juxtaposed the two words in The Tempest, a British educator named Richard Mulcaster wrote, "Nature makes the boy toward, nurture sees him forward." Three hundred years later, Galton turned the pairing of the words into a catchphrase. It caught on like a clever advertising slogan and became part of our language.

But the true father of the nurture assumption was Sigmund Freud. It was Freud who constructed, pretty much out of whole cloth, an elaborate scenario in which all the psychological ills of adults could be traced back to things that happened to them when they were quite young and in which their parents were heavily implicated. According to Freudian theory, two parents of opposite sexes cause untold anguish in the young child, simply by being there. The anguish is unavoidable and universal; even the most conscientious parents cannot prevent it, though they can easily make it worse. All little boys have to go through the Oedipal crisis; all little girls go through the reduced-for-quick-sale female version. The mother (but not the father) is also held responsible for two earlier crises: weaning and toilet training.

Freudian theory was quite popular in the first half of the twentieth century; it even worked its way into Dr. Spock's famous book on baby and child care:

Parents can help children through this romantic but jealous stage by gently keeping it clear that the parents do belong to each other, that a boy can't ever have his mother to himself or a girl have a father to herself.

Not surprisingly, it was psychiatrists and clinical psychologists (the kind who see patients and try to help them with their emotional problems) who were most influenced by Freud's writings. However, Freudian theory also had an impact on academic psychologists, the kind who do research and publish the results in professional journals. A few tried to find experimental evidence for various aspects of Freudian theory; these efforts were largely unsuccessful. A greater number were content to drop Freudian buzzwords into their lectures and research papers.

Others reacted by going to the opposite extreme, dumping out the baby with the bathwater. Behaviorism, a school of psychology that was popular in American universities in the 1940s and '50s, was in part a reaction to Freudian theory. The behaviorists rejected almost everything in Freud's philosophy: the sex and the violence, the id and the superego, even the conscious mind itself. Curiously, though, they accepted the basic premise of Freudian theory: that what happens in early childhood -- a time when parents are bound to be involved in whatever is going on -- is crucial. They threw out the script of Freud's psychodrama but retained its cast of characters. The parents still get leading roles, but they no longer play the parts of sex objects and scissor-wielders. Instead, the behaviorists' script turns them into conditioners of responses or dispensers of rewards and punishments.

John B. Watson, the first prominent behaviorist, noticed that real-life parents aren't very systematic in the way they condition their children's responses and offered to demonstrate how to do the job properly. The demonstration would involve rearing twelve young humans under carefully controlled laboratory conditions:

Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I'll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select -- doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief, and, yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors.

Fortunately for the dozen babies, no one took Watson up on his proposal. To this day, there are probably some aging behaviorists who think he could have pulled it off, if only he had had the funding. But in fact it was an empty boast -- Watson wouldn't have had the foggiest idea of how to fulfill his guarantee. In his book Psychological Care of Infant and Child he had lots of recommendations to parents on how to keep their children from being "spoiled" and how to make them fearless and self-reliant (you leave them alone and avoid showing them affection), but there were no suggestions on how to raise children's IQs by twenty points, which would seem to be an important step toward getting them into medical or law school, in preparation for the first two occupations on Watson's list. Nor were there any guidelines for how to make them choose medicine over law, or vice versa. When it got right down to it, the only thing John Watson had succeeded in doing was to produce conditioned fear of furry animals in an infant named Albert, by making a loud noise whenever little Albert reached for a rabbit. Although this training no doubt discouraged Albert from growing up with the idea of becoming a veterinarian, he still had plenty of other career options to choose from.

A more promising behavioristic approach was that of B. F. Skinner, who talked about reinforcing responses rather than conditioning them. This was a far more useful method because it didn't have to make do with responses the child was born with -- it could create new responses, by reinforcing (with rewards such as food or praise) closer and closer approximations to the desired behavior. In theory, one could produce a doctor by rewarding a kid for bandaging a friend's wounds, a lawyer by rewarding the kid for threatening to sue the manufacturer of the bike the friend fell off. But what about the third occupation on Watson's list, artist? Research done in the 1970s showed that you can get children to paint lots of pictures simply by rewarding them with candy or gold stars for doing so. But the rewards had a curious effect: as soon as they were discontinued, the children stopped painting pictures. They painted fewer pictures, once they were no longer being rewarded, than children who had never gotten any rewards for putting felt-tip pen to paper. Although subsequent studies have shown that it is possible to administer rewards without these negative aftereffects, the results are difficult to predict because they depend on subtle variations in the nature and timing of the reward and on the personality of the reward recipient.

Genius is said to be 99 percent perspiration, 1 percent inspiration. Behaviorism focuses on the perspiration and forgets about the inspiration. Tom Sawyer was a better psychologist than B. F. Skinner: by letting his friends reward him for the privilege of whitewashing the fence, he not only got them to do the work, he got them to like it.

I don't think Watson really wanted a dozen healthy infants to experiment with. I think his request was just a vainglorious way of expressing the basic belief of behaviorism: that children are malleable and that it is their environment, not innate qualities such as talent or temperament, that determi...

Combining insights from psychology, sociology, anthropology, primatology, and evolutionary biology, she explains how and why the tendency of children to take cues from their peers works to their evolutionary advantage. This electrifying book explodes many of our unquestioned beliefs about children and parents and gives us a radically new view of childhood.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurPocket Books

- Date d'édition1999

- ISBN 10 0684857073

- ISBN 13 9780684857077

- ReliureBroché

- Nombre de pages480

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 2,75

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

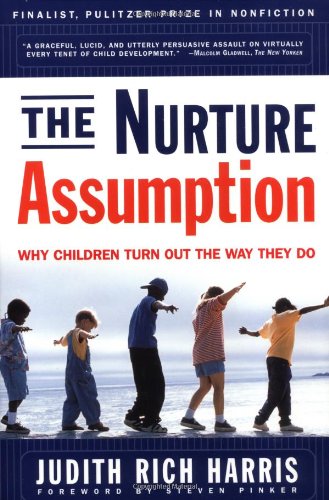

The NURTURE ASSUMPTION: Why Children Turn Out the Way They Do

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. Brand New Copy. N° de réf. du vendeur BBB_new0684857073

The NURTURE ASSUMPTION: Why Children Turn Out the Way They Do

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. Buy for Great customer experience. N° de réf. du vendeur GoldenDragon0684857073

The NURTURE ASSUMPTION: Why Children Turn Out the Way They Do

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard0684857073

The NURTURE ASSUMPTION: Why Children Turn Out the Way They Do

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think0684857073

THE NURTURE ASSUMPTION: WHY CHIL

Description du livre Etat : New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.15. N° de réf. du vendeur Q-0684857073