Articles liés à Singing Lessons: A Memoir, of Love, Loss, Hope and...

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNWhen I heard the news of my son's death, I was standing in the foyer of my apartment in New York among the paintings and the flowers and the photographs of my family, in the beautiful space I have called home for twenty-eight years. Louis was in Washington, D.C., making a presentation for the Korean War Veterans Memorial Wall. He had called at six that evening, saying he would take the noon shuttle and be home by two the following day. Meanwhile I waited for my son to call me back from St. Paul. I had left a number of messages for him. I worked for a while longer and ate a solitary dinner around eight. I was alone but contented, a normal, quiet evening.

My last.

The doorbell rang at around eight-thirty. I wasn't expecting anyone and a strange feeling came over my heart. I peeked out the keyhole and saw my brother Denver and sister-in-law Allison standing in the hallway. I let them in. There was a deep silence and I knew from my brother's eyes what had happened. He didn't even have to speak. He took me in his arms and my world changed forever. I heard a scream from some primitive place I had not known before.

I clung to my brother, slowly becoming aware of the scent of roses and violets from a bouquet on the hall table; there was a sweet, lingering taste of mint in my mouth; my eyes focused on a photograph of my brothers and sister in a silver frame next to the flowers. I heard the sound of a siren on a Manhattan street below, and then my eyes moved to a picture of my son as a child, his red hair cropped close to his head and his big blue eyes looking out at me. Our eyes held each other and I caught my breath for what seemed an eternity, knowing the world was turning to darkness and I would never see it or hear it or live in it the same again.

My brother and sister-in-law comforted me as best they could. I stood up. I sat down. I laid on the bed. Allison made tea. I wept. My brother had tracked Louis down in Washington and told him the terrible news and Louis had lovingly arranged for Denver to tell me about Clark's death in person so that I wouldn't have to hear it on the telephone. My mother had been called, my siblings -- the family Clark had loved so much and who had loved him all now knew that he was gone.

I had thought we had won this battle, that the darkness had been averted. But it was not to be. Denver, Allison, my nephew Joshua and my niece Corrina and I flew to the Twin Cities the next day, where Louis joined us. The rest of my family arrived from far-flung cities to gather at the mortuary, putting their arms around me and each other; brothers and sister, mother, cousins, holding me close.

The tears for this terrible loss would keep coming in the days and years to follow, dropping like rain from the foggy valley through which I would walk, the valley of the shadow of death.

The world was suddenly the enemy, the place where this could happen, where it had happened. My knees wouldn't hold me, nothing could -- but my loving family held me, and we held on to each other. None of us were sure we would survive Clark's death, floating on this new and terrible ocean that had sprung up around us, an ocean full of storm and sorrow.

In St. Paul, snow had fallen, a heavy white mantle covering every statue in the city, every tree, every lamppost. A whiteness and a cold penetrated my nostrils and my breath froze, holding back even my tears after a while. The weather seemed to foretell the end of a world. This must have been what it was like for primitive peoples, this disappearing of the sun, the brightness and light gone. The weight of my son's death, like the weight of the white snow, stilled every bird, froze all life. Nature wanted to stop, time wanted to stop, life had stopped. For my son, there would be no thaw.

January 16, 1992, Thursday. Bitter cold. Snow. St. Paul, Minnesota

The snow has fallen on the pine trees, and their branches bend, heavy with white drifts. I stand at the door of a long, narrow room covered with a green carpet, my fingers tremble and my knees shake. The walls of the room are hung with flowered wallpaper, a design of green ivy on a cream background. Far away, at the end of the room, is the end of the road, the end of my dreams; a body under a white sheet lies lengthwise on a marble slab and I struggle forward toward the ancient, familiar figure as though climbing a great mountain, as though swimming an endless sea. I walk against the wind, I fight tides. The distance I travel is the breadth of the known world, to the furthest galaxy, to the end of time, to the end of life.

There, I see my son's freckled face, his shining red hair in plaits falling from his high forehead. Red streaks line his pale skin, the mark of the carbon monoxide, the stamp of death. He is some warrior from another time. I kiss his forehead, cold as marble under my lips, and sink to my knees. My tears fall on my hands and on my shoes, then on the snow and on the coverlet of the bed in the hotel in which I lay, my eyes open, waiting, trying to keep breathing. I keep thinking, this is not him, there is some terrible mistake, he is not dead, he cannot be gone.

The next day, Clark lay under the aspen leaves, under the bed of white roses on the lid of the carved wooden casket. Under the baby's breath and intertwined white rosebuds, Clark kept his silent vigil at his funeral.

A suicide.

Louis talked to the press, keeping the newspapers and reporters at bay. He and my brothers handled details at the mortuary, letting me think I was making the decisions myself.

A woman at the mortuary, kind and gentle, told me she would take care of my son.

Alyson, my daughter-in-law, was very shaky and seemed to be in a daze, little Hollis was opened-eyed, aware of everything. She and her mother had discovered Clark's body, as he must have known they would. I knew both must still be in shock. All of us were moving through a dream. A nightmare. Our friend Terry helped Louis order flowers and put the obituary together. We chose an urn for my son's ashes and picked out the casket. The terrible chores. God must have lifted us through these because none of us could do this thing. Together we planned the funeral, Louis inviting Alyson and all of Clark's friends and family to speak. I didn't know if I could walk through this fire.

It was all such a waste, it was all such a tragedy.

Louis spoke with tender words about his stepson. Then he invited everyone to share, Quaker-style. Nearly two hundred of Clark's friend's and family were there and many spoke of his loving spirit. The love for my son poured out in floods of emotion as Clark's friends memorialized my beautiful son. Everyone who loved Clark knew that he fought with his demons, knew that he had lived close to the angels.

After my daughter-in-law spoke, Rosalind, Clark's halfsister, stood, wearing my son's face, his fine bones, his gentleness, his beauty. She is tall like my boy, thin as he was, beautiful, her face pale under her pale complexion, her hair long and strawberry, as his had been. She talked of the secret suicide they shared, the death of their paternal grandfather Al. There was a sound, almost a sigh, in the room as she spoke.

"I see my father and his brother, as grandfather died, taking in that last breath, breathing in as he breathed out, and holding that breath for forty-five years. With Clark's death, that breath can finally be let out." Rosalind had earned the right to speak the truth, and truth was what was needed.

Under the white lilies and roses and aspen leaves atop his coffin, I seemed to see Clark's red hair shimmering all through the ceremony. At the end the bagpiper played "Amazing Grace." I sang "Amazing Grace" for my son for the last time.

At home in New York the mortuary sent me his clothes, the jeans they cut off him, the belt, the green and gray shirt, all smelling of carbon monoxide. They were in a brown shopping bag with his boots and his black socks. I wondered if my son had dressed for death. They gave me the leather briefcase in which were the keys to his desk at work, words to the last songs he had written.

It took me four years to get rid of the clothes. I gave them to a shelter. I could not, ever, look at them again, except a white cashmere sweater I have come to love holding next to my skin.

It was, for me, the saddest day of my life. It seemed to be the end of the world.

Sometimes it seems to me the nightmare began the day I bought my son the Subaru. It was on one of my visits to Minnesota, a cold, bright winter day in 1987. The Twin Cities sparkled under that polished sky of the land of a million lakes, so clear and crisp it made your eyes ache. Our hearts were light and our voices filled with love and cheer. Life was so good.

The station wagon was a dark, almost charcoal color called umber -- a solid car, good for the cold Minnesota winters. My son was bundled into a hooded, fur-collared parka and I was draped in my black cashmere coat with the purple lining, a coat I use every winter -- warm as toast, comforting in hotel rooms. I spend a lot of time in hotel rooms, on the road, doing concerts. My son said he might have been a rock-and-roll singer but he knew from the life his mother led that it wasn't an easy one.

Clark was excited about the Subaru, looking at me from his clear, untroubled face with anticipation and pleasure.

I looked at him intensely as though to memorize his metamorphosis. He was about five nine, with freckles in a scattering across his nose and arms that deepened in the summer sun. He could never get a tan. At thirty-two, he was a lanky figure in the pictures from Holly's wedding, the replica of his father, Peter, even to the way his figure bends, just so, from the waist, leaning over to hear you speak, leaning back to laugh. It took my breath away when I saw that. My heart skipped a beat.

Clark had always had a soulful singing voice, dark and sweet, unique in the way he played the notes and the way his voice meandered over the words, lovingly. He had a great sense of humor and an infectious laugh. His intelligence, evident at an early age, illuminated a deep sensitivity to others' pain, and to his own.

He was a redhead, a shade of red that tended more to strawberry than firehouse. At times in his life his hair grew down to the middle of his back. He cut it at least twice in his adult life, severing the luscious strawberry hank in a twist a foot and a half long. For a while when Clark was in his late twenties and early thirties, he wore his beautiful hair short, chopped off at the root. At his death, he was wearing it long again, down to his shoulders. How could he do it, just like that? Grow his hair, cut his hair? Take his life?

Clark understood me as no one else could. He understood the celebration as well as the troubles that the journey of our lives together brought. We were bound so very tight by the good things, as well as by the demons. It was as if he had lived before, experienced many things, and could see beyond the moment with a clarity that was startling. At his darkest time, he could still be a shining light and a beacon of hope. Clark was the person with whom I had been through everything. I loved him more than anyone.

Many people loved him. Who wouldn't love him? Teachers he had in the schools he went to, friends I didn't know, peers he had helped, stop me in the street or in church or write to me and say how much he meant to them. He changed people, made them think, turned their eyes and their thoughts inward. He understood why life was funny, why loving animals is a requirement, why, as Norman Maclean says in "A River Runs Through It," fly-fishing is akin to religion. Fishing was in his genes, from his father, his uncles, probably his great-grandfathers, and he took to it with such zeal. In my mind's eye I see him, going up to the lake country in the Subaru, casting in his waders, walking through rippling waters, returning home with trout or bass, cooking them himself for Alyson and the baby. He would practically throw himself into the middle of a lake if that is what it would take to catch that fish.

Clark always loved a good car and since he was healthy, he wasn't about to run this one into a mountain or drive it over a bridge embankment or roll it on a curve or put dents in the frame, as he had done in the terrible old days with my brother Dave's cars.

My son was a responsible man these days. He would soon be a parent. I was co-signing the loan for the station wagon that was going to get him around in the snows and the heat of Minneapolis with his wife and his baby. Those early, terrible days were only memories now, part of a story he might tell his child, the mesmerizing bedtime tale of how her father had come back from the grave.

It was a beautiful car, the Subaru. My son stroked the silky surface of the softly molded frame, complimented the paint job, checked out the tires and the big, generous backseat. We drove the car around the neighborhood for a while. On the way back to the office, we talked about Clark's job at the trade college in nearby Minneapolis where he worked in the computer repair shop. I knew he wanted to go back to school but was happy to settle for a good job where he was learning a lot about computer technology.

The computers, and the baby, and Clark's wife, Alyson, and the groceries and the fly-fishing rods for the northern Minnesota lakes would all fit into the Subaru, with room to spare. He looked at me and said, "Yes, this really is the one," as we sat in the office of the dealer, signing papers, talking and laughing easily over mugs of steaming coffee the salesman had brought, clutching sugar, milk, wooden stirrers, napkins and the co-signature papers in his hand. Nothing worth doing, Clark and I always agreed, could be done without a good cup of coffee.

I watched my son's face. His eyes were bright as he glanced at me over his coffee cup, skin shining with health, weight on his thin bones, life and hope and health in his body. How different from the pale, frightened boy who had traveled to Minnesota to find a new way of life. He laughed at something the car dealer said as he took the pen in his hand and signed his name. I signed on the dotted line as well. Clark was the proud owner of a brand-new, spacious, buttery-finished Subaru station wagon.

On my visits, my son would pick me up at the airport in the Subaru. We would hug each other, joyful to be in each other's presence. Clark was proud of the Twin Cities airport valet parking, unique in airports. He would pack my heavy luggage with its wheels, along with my computer and handbags, into the back of the umber station wagon and we would tool on down the highway that runs by the river, the great Mississippi winding south through Minneapolis, on down toward the Gulf of Mexico. On the drive, our voices rose and fell in pleasure. No one laughed at my jokes the way Clark did. We thought the same kind of things funny, the same kind of things sad.

We would arrive at the ramp to his tree-lined street, turning into the driveway of the house in Crocus Hill, where we would stop, perhaps admiring the new porch or the work Clark was doing on the house; hugs with his wife Alyson and kisses and hugs with the baby, Hollis; then Clark would pour me a cup of his black, strong-brewed coffee. We would visit, talking about the past, about the future, about the rich and wonderful present.

Louis and Clark became close in those years and sometimes he would join me in my visits. Clark and Louis talked as friends, and Clark would ask Louis' advice about work, about school. Sharing was important to both of them. T...

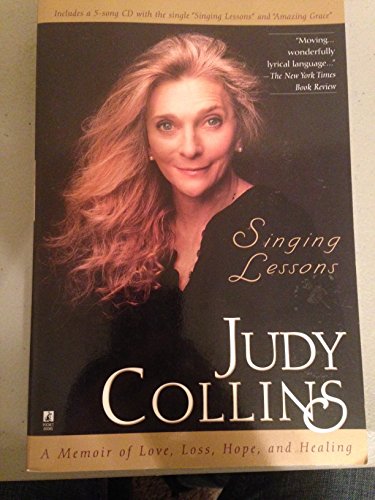

"Before I suffered a major catastrophe, I had no way of understanding the depth to which the soul is shaken, the exterior shattered, the interior made vulnerable and raw. Perhaps this is the way the wound works, to open us up so that we can feel and experience the depths, and having gone there, climb to heights we could never imagine...." It was the suicide of her son Clark in 1992 that signaled the slow dismantling of Judy's life, "the end of the world." But in its wake came a choice: to become another victim of the tragedy or to emerge victorious. Judy chose victory, freeing her heart to appreciate every precious moment of life, and see the gift of memory for the miracle it is.

With quiet grace and uncommon candor, Singing Lessons reveals some of those miracles -- Judy's memories of places, people, triumphs, and tragedies. From meeting Gloria Steinem and John F. Kennedy to dining with Bill and Hillary Clinton and spending an extraordinary night in the Lincoln bedroom; from recalling the lessons of her beloved music teacher of thirty-two years, Max Margulis, to reflecting on her marriage to Louis Nelson, lover and soulmate for twenty years; and from her fierce battles with her own demons to heartfelt remembrances of her son, Judy shares herself, in the sweet, clear voice that is as true as her music, with the insight her fans have come to know from her lyrics.

More than an intimate memoir, Singing Lessons is the triumph of a keenly observant, brilliantly gifted artist -- a deeply affecting and eloquently written journal of a woman determined to keep her heart open, her spirit intact, and all the elements of her life in harmony. It is the heart and soul of Judy Collins.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurPocket Books

- Date d'édition1999

- ISBN 10 0671003984

- ISBN 13 9780671003982

- ReliureBroché

- Nombre de pages346

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 4,14

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Singing Lessons: A Memoir, of Love, Loss, Hope, and Healing [With 5-Song CD]

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : New. New softcover in printed wraps. Text is clean and free of marks or underlining. Includes photo plates and CD. 368 pp. Fast shipping in a secure book box mailer with tracking. Singing Lessons is Judy Collins's life statement, complete with stories of her childhood, the music industry, her marriage to a man she had been living with for 17 years, her trips to Vietnam and Bosnia, and her night in the Lincoln bedroom. With rare candor and the insight her fans have always glimpsed in her lyrics, she looks back on a rich and extraordinary life -- full of both successes and failures -- with sorrow, joy, and wisdom. Chapters are separated by mediations on death and rebirth she wrote in the period after her son's suicide. N° de réf. du vendeur 101116

Singing Lessons (w/CD)

Description du livre Etat : New. . N° de réf. du vendeur 52GZZZ00U2UQ_ns

Singing Lessons (w/CD)

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : New. Brand New!. N° de réf. du vendeur VIB0671003984

SINGING LESSONS (W/CD)

Description du livre Etat : New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.25. N° de réf. du vendeur Q-0671003984